His snatch catch was so cool.

Rickey Henderson would take a routine fly ball, usually one of baseball’s most yawn-inducing endeavors, and turn it into a showcase. A flex. Of his elite hand-eye coordination. Of his dexterity. Of his swag.

He’d swipe his glove from left to right across his face, swatting away the mundanity of the act, at just the right time to snatch the ball out of the air. He’d then slap the glove against his right hip, toss the ball to his throwing hand and smoothly launch the ball back into the infield.

Rickey couldn’t just let the ball land in his glove unceremoniously. And the message behind his method was loud and clear. Rickey had his own ethic in a sport that so often upholds uniformity and decorum as sacred.

However unnecessary it may seem, however many feelings may rankle as a result, it is of critical importance to reveal one’s capacity and depth of talent. It is a long-term advantage to disavow any notions of comparability, to rebut any stereotypes of inferiority, and to declare a greatness that for any reason might be denied.

In honor of Rickey, let’s put this in simpler terms: Sometimes, you gotta let ‘em know.

On this Christmas Day, we wish a Happy Birthday to a fallen legend, whose gift to our world extends beyond numbers. Rickey isn’t just the greatest leadoff hitter ever. He is more than a Hall of Fame baseball player. He is an icon. A singular figure who only needs a singular name. Rickey. He is an emblem of the culture, an ambassador for the self-actualization so many needed to see.

Appreciating Rickey Henderson

Rickey was unashamed of his brilliance, which meant he couldn’t be dissuaded from proclaiming it. And he was the best at not-so-subtle proclamations that he was the one. Rickey gold-plated his greatness. Karats paired with a stick that produced 297 home runs and a .279 career batting average.

And when you’re a fan of Rickey Henderson, borrowing that same aura is normal.

So many of us did. Growing up in Rickey’s city, also hailing from Oakland Technical High School, running around the same streets and playing at the same parks, it was easy to see Rickey’s impact. I didn’t play a lot baseball because the only thing I could do was catch. It sometimes looked as if I couldn’t catch because I dropped so many easy outs trying to snatch catch like Rickey. Tryna let ’em know.

Every Bay Area kid was claiming No. 24 as their cousin. Everybody wanted to steal bases. Everybody copied his mannerisms.

His collar-popping was so cool.

Ahhhh, man. You had to be there to understand the dopamine rush it was to watch Rickey crush a no-doubter. He’d immediately go from a lead-off hitter to a costar in a Pam Grier film. That man would flip his bat, hop, step back, do a li’l two-step, all while popping an invisible collar on his way to first base. Then he’d round the bases so smoothly and delicately, like he didn’t want to crease his expensive ‘gators.

(Jeff Carlick / MLB Photos via Getty Images)

Back then, many didn’t like his antics. He was called every Oscar Mayer product on the market. Baseball couldn’t stand a showboat. But Rickey didn’t care. And we love him for not caring.

An important social context to Rickey can’t be ignored. His rise to stardom came on the heels of a surge of Black affluence in the 70s and 80s. While still behind other groups and still on the business end of a widening wealth inequality gap, Black people made some financial progress following the Civil Rights Movement and the ensuing Black Power Movement — which was especially prominent in Oakland. Many found success. They worked to buy homes. They had good, stable jobs. They bought Cadillacs, nice clothes, jewelry. The freedom, the audacity, to announce yourself as a talented, accomplished and responsible member of society was an earned right. It took too much to get there to “act like you’d been there before.”

At the same time, during Rickey’s stardom, the crack epidemic was ravaging some of those same communities. Many were losing all they and their parents worked for in neighborhoods intentionally flooded with cheapened cocaine. The children of this generation-consuming disaster grew up witnessing clear gains of Black people being undermined. So imagine what it meant to experience Rickey. To draft off his confidence. To imagine what was possible based on what he presented.

He let generations know it was reasonable to be confident, to be proud. Even to be arrogant. It’s suitable, preferable even, to affirm your own excellence — especially when your success came at improbable odds. Knowing what it’s like to be looked down upon, to get that stare of disgust at the very sight of you, to feel the absence of expectation over your life, means understanding the liberation in making it clear you belong among the best.

Showmanship isn’t inherently an absence of class. Perhaps it’s best viewed as the introduction of a new class entering the fellowship.

That’s why his third-person lingo was so cool.

No way in this world Rickey would be embraced in the circles where he is now so beloved if he weren’t excellent at baseball. He didn’t have a pedigree that would gain entry.

He was born in Chicago in the back of an Oldsmobile on Christmas Day, the ‘hood’s version of a manger. He didn’t come from a well-to-do family. He spent some of his formative years on a farm in Pine Bluff, Ark., where they lived with his grandmother after his biological father moved west. He was 10 years old when he moved to Oakland. His mother went first to get settled then sent for her fourth son, Rickey Nelson Henley. He got the name Henderson his junior year of high school, after his mother married Paul Henderson, the man Rickey would deem his father, as chronicled in his 1992 autobiography “Off Base: Confessions of a Thief.”

These Hendersons weren’t wealthy in the Bay Area, either. And Rickey didn’t speak well enough to impress. Nor did he bother diminishing himself. He wasn’t as nonthreatening as the dominant culture would’ve required. That is to say, none of this magnificence was expected of him by society.

That’s why, sometimes, you gotta let ‘em know. He spoke about himself as if he were name dropping a major figure he knew. As if he were evoking the clout of a superstar. It is wild to speak of oneself in the third person — unless one grows to such magnitude as to make the practice a charming quirk. The entire time, Rickey was imprinting himself on our psyche, giving us fodder with which to honor him.

Rickey always knew he was somebody special. He had the boldness to operate with that knowledge. And those who spent time around him know his brand of special wasn’t limited to the diamond. He was incredibly kind. He was jarringly humble. He was hilarious in his own way. He was a man of the people.

It was common to spot Rickey out and about in Oakland. A tangible giant. He’d regularly oblige a handshake, a photo, an autograph, or a dap. Once, I ran into him at a gas station. He looked to be in a bit of a hurry when I yelled his name from my pump. He walked with an extra pep in his step as he gave me a wave and a smile, then put his finger in front of his mouth. Kindly asking to keep his presence on the low. Rickey had somewhere to be, clearly.

When a woman asked me who he was, Rickey’s polite request was instantly disregarded. Unintentionally of course. It was a reflex to give the only proper response when asked such a question.

That is Rickey Henderson, one of the greatest baseball players, Oakland Tech’s finest and a true legend from The Town.

Moments later, as I got into my car, Rickey was taking a picture with the woman and a boy. With a smile across his face, he shot me a look that made me laugh. I apologized to him in my heart.

My bad, Rickey. But sometimes, you just gotta let ‘em know.

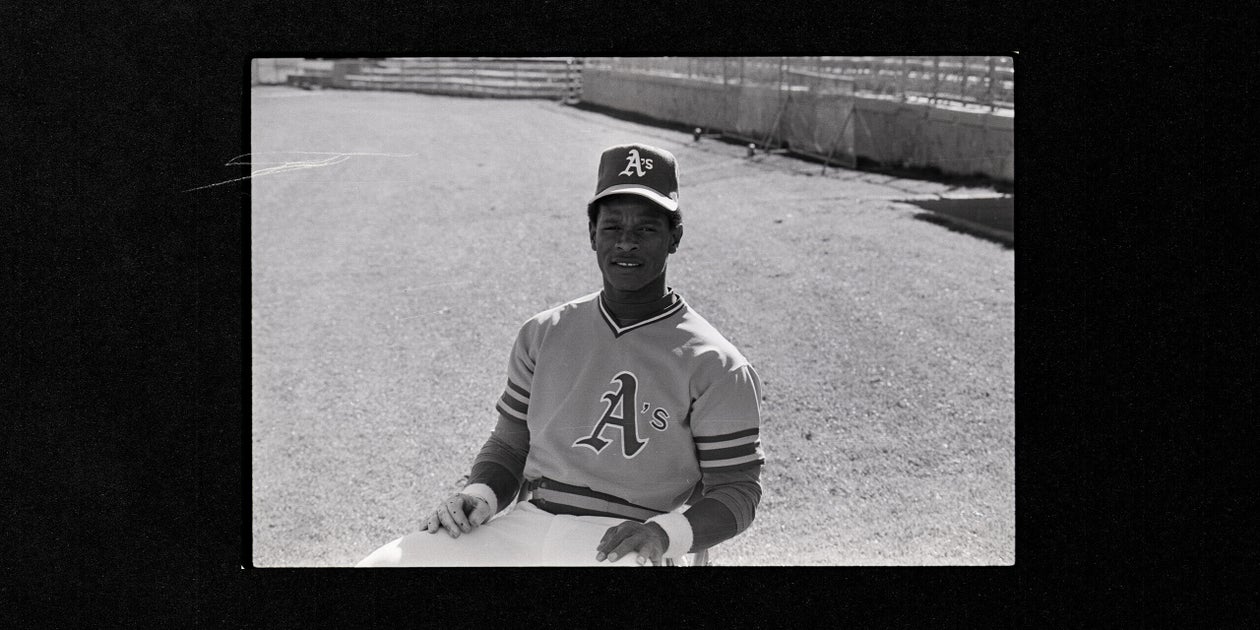

(Top photo of Rickey Henderson in 1980: Bettmann / Getty Images)