Travel from China to the United States with Haiwen and Suchi, lovers separated by time and one pivotal decision, from the ’40s to present day. In this excerpt, wander the vividly painted streets of wartime Shanghai with vendors, early risers, and troubled minds, and meet heartbroken Haiwen and Suchi on the cusp of the event that will separate them by time and distance until they meet again 60 years later.

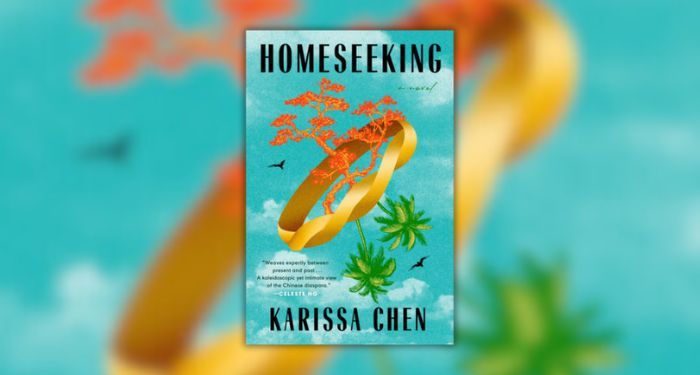

Homeseeking by Karissa ChenAn epic and intimate tale of one couple across sixty years as world events pull them together and apart, illuminating the Chinese diaspora and exploring what it means to find home far from your homeland. A single choice can define an entire life. Haiwen is buying bananas at a 99 Ranch Market in Los Angeles when he looks up and sees Suchi, his Suchi, for the first time in sixty years. To recently widowed Haiwen it feels like a second chance, but Suchi has only survived by refusing to look back. Suchi was seven when she first met Haiwen in their Shanghai neighborhood, drawn by the sound of his violin. Their childhood friendship blossomed into soul-deep love, but when Haiwen secretly enlisted in the Nationalist army in 1947 to save his brother from the draft, she was left with just his violin and a note: Forgive me. Homeseeking follows the separated lovers through six decades of tumultuous Chinese history as war, famine, and opportunity take them separately to the song halls of Hong Kong, the military encampments of Taiwan, the bustling streets of New York, and sunny California, telling Haiwen’s story from the present to the past while tracing Suchi’s from her childhood to the present, meeting in the crucible of their lives. Throughout, Haiwen holds his memories close while Suchi forces herself to look only forward, neither losing sight of the home they hold in their hearts. At once epic and intimate, Homeseeking is a story of family, sacrifice, and loyalty, and of the power of love to endure beyond distance, beyond time. |

Overture

April 1947

Shanghai

In the last violet minutes of the disappearing night, the longtang wakes.

The neighborhood’s familiar symphony opens with the night-soil man’s arrival: the trundle of his cart on the uneven road, the chime of his bell. With a slurry and a swish, he empties the latrines left in front of uniform doors and sings a parting refrain. In his wake, stairs and hinges creak; women peek out into the alleyway to claim their overturned night stools. Crouching, they clean silt from the wooden buckets: bamboo sticks clock, clamshells rattle, water from back-door faucets glugs and splatters. By the time they have finished, the sugar porridge vendor has emerged, announcing her goods in repetitive singsong as she pushes her cart. Later, the others will join her: the tea egg man, the pear syrup candy peddler, the vegetable and rice sellers, each with their own seasoned melodies. But for now, it is her lone call that drifts through the lanes of Sifo Li.

She passes the Zhang family shikumen, the sixth row house along this perimeter. Inside, on the second floor, sixteen-year-old Suchi sleeps fitfully after hours of weeping, her slender limbs twisted around the thin cotton sheet, her sweat seeping into the mattress. She is mired in a nightmare in which Haiwen no longer recognizes her. A delicate crust of dried tears rims her lashes.

Next to her is the older Zhang daughter, Sulan, who snuck back home only an hour earlier. Her skin is sticky with the smell of smoke and alcohol and sweat. She sleeps peacefully, dreaming of dancing in a beautiful dress of plum taffeta and silk, arm in arm with her best friend, Yizhen.

In the room above, her father, Li’oe, lies sleepless, troubled by uncertainties. He wonders how much his stash of fabi has depreciated overnight, how much gold he might buy off the black market with what currency he has left. He weighs the continued cost of running his bookstore, of printing the underground journals—all he is taking from his family, not to mention the danger—and for a moment guilt licks at the edge of his thoughts. He regrets now pawning that little ring he purchased the day Suchi was born, two delicate twists of gold braided into one, something he’d saved for her dowry.

But Sulan had insisted she’d found the perfect secondhand cloth to make Suchi a qipao for her birthday, and he’d agreed to give Sulan the money. Now he thinks only of how valuable that loop of gold has become.

Beside him, his wife, Sieu’in, pretends to sleep, pretends to be unaware of her husband’s nervous shifting. She inventories the food left in their stores—half a cup of rationed gritty red rice, a handful of dehydrated mushrooms, cabbage she pickled weeks ago, radish scraps boiled to broth, a single cut of scallion she has coaxed into regrowth in the spring sun. She can stretch these ingredients for a week, maybe a week and a half—she will make a watery yet flavorful congee, and when none of that remains, she will empty the rice powder from the bag and boil it into milky liquid offering the illusion of nourishment. After that? She won’t add to her husband’s worries by asking him for more money, she decides. She has a few pieces of jewelry remaining—the jade bracelet that presses coolly against her cheek now, for instance. Her mother gave it to her from her own dowry, and its color is deep, like the dark leaves of the green vegetables she so desperately craves.

A floor and a half below, in the pavilion room, Siau Zi, their boarder and employee, is dreaming of the older Zhang daughter. Sulan smiles invitingly, her lips painted red, her hair permed and clipped. He is effortlessly charming in this dream; for once he says the right things to make her adore him. I can take care of you, he tells her, I’ll be somebody in this new China, you’ll see, and she sighs into his embrace.

Outside Siau Zi’s window, the sky is turning a violent shade of pink. The neighborhood’s song shifts its layers as its inhabitants dust off their dreams and rise. Lovers murmur. Coals in stoves crackle. Oil sizzles in a pan, ready to fry breakfast. Doors groan open, metal knockers clang against heavy wood. A grandma sweeps the ground in front of her shikumen, the broom scratching a staccato beat against the cobblestone. A child cries, seized from sleep.

The porridge vendor continues her route. In vain, she calls out, remembering a time when her goods were beloved by the children of this neighborhood, a time before the wars, when she could afford to use white sugar and sticky rice, when adding lotus seed hearts and osmanthus syrup was standard instead of a great luxury. As she nears the shikumen where the Wang family lives, she pauses, recalling how the young son particularly delighted in her dessert. She bellows out twice: Badaon tsoh! Badaon tsoh!, deep throated, as passionate as if she were calling out to a lover—but she is met with the dim stillness of the upper windows. After a moment, she blots her sleeve against her forehead, leans into her cart, and continues on her way, the echo of her song trailing behind her.

But the Wang household is awake.

Yuping has not slept the entire night; her eyes are puffy and dark. She tries to cover her despair with makeup, but when she catches her reflection in the mirror, the tears resume. Her husband, Chongyi, pretends not to notice. He dresses quietly, parts his salt-and-pepper hair to one side with a fine-toothed comb, and slicks strays with oil. He thinks to gift his son, Haiwen, this comb. It is carved from ivory and inlaid with mother-of-pearl, a frivolous vanity he has held on to after all these years when they have sold so much else.

In the next room, their eleven-year-old daughter, Haijun, rummages through her music box, searching for a memento to gift her big brother. Onto the floor, she hurls the paper cutout dolls, the hair ribbons, the red crepe flower she palmed from a store’s decorative sign. All these so-called treasures and she has nothing worth giving him. In a fury, she balls herself beneath her blanket, hoping to suffocate in the damp jungle of her breath.

In the attic room, the eldest son, Haiming, and his pregnant wife have been up since before dawn. The room is foul with the stench of bile, Ellen having vomited twice. She doesn’t want to go to the train station later, she tells her husband. But Haiming only looks at her, silent and somber.

Haiwen is first to descend the stairs. In his new uniform, his arm pits are already sweating through the heavy, unforgiving fabric. He steps outside, into the modest courtyard of their shikumen, and looks up at the expanse of sky. The pink is receding, giving way to a noncommittal blue. In several minutes, nothing of that brilliant color will remain, only a veil of thin cloud, like a layer of soy milk skin.

He listens to the longtang’s symphony, this comfort he has grown up with. He closes his eyes and sees it all, no longer a symphony but a movie, one more vibrant than any he’s attended at the cinema: The cobblestone alleys crammed with wares and possessions. The neighborhood children, laughing as they chase one another. The barber they nearly knock over, Yu yasoh, and his client, Lau Die, whose crown is sparse but beard is full. The nearby breakfast stall opened daily by Zia yasoh, and the rickshaw driver who sits slurping a bowl of soy milk on a low stool. The second-story window that opens so Mo ayi can call to a passing vendor, who stops as she lowers a basket with a few coins in exchange for three shriveled loquats. Loh konkon and Zen konkon in the middle of it all, the two men oblivious to the surrounding hubbub as they mull over their daily game of xiangqi, a ritual that continues uninterrupted as it would on any other day.

But it is not any other day.

Haiwen opens his eyes.

Today is the day he is leaving.

In another two hours he will be on the train with the other enlistees, a bulging backpack pressed against his belly, a photograph of Suchi against his breast, a tremble in his heart, waving at the receding image of his family. The longtang of his childhood, Sifo Li, will be behind him; Fourth Road, with its bustling teahouses and calligraphy stores, will be behind him; soon, Shanghai, too, will be behind him. For years afterward, he will riffle through his memories of this place he considers home, layering them on top of one another like stacks of rice paper, trying to remember what was when and never quite seeing the full picture.

For now, Haiwen closes his eyes again. His mind traces the alleyways he knows so well, the well-trod path between his house and Suchi’s, cobblestones upon which he will walk one last time in the coming minutes: The four-house expanse between his shikumen and the first main lane on their left. The right turn down the lane that intersects with the one that heads toward the west gate. Another left, another main artery. The straight long distance toward the south gate’s guojielou, the turn right before the arched exit. The five plain back doors until the painted bunny comes into view, its flaked white outline wringing a pang in Haiwen’s chest. He will leave his violin here: he sees himself setting it down, laying it against the chipped

paint as tenderly as he imagines a mother abandons a beloved baby.

He knows he will look up at the second- floor window. Suchi’s window. Its vision dredges an unbearable loneliness in him.

He squeezes his eyes tighter, tries harder, and what comes next is impossible: He is peering through her window, gazing upon her as she sleeps. In another moment, he has prised open the panels and is inside her room. She is dreaming, she is talking to him in her sleep. He places a palm against her cheek, strokes a thumb across the soft velvet of her skin. He takes in the fringe of her lashes, the bud of her mouth. A mouth he wishes he had remembered to kiss one final time. He wants to remember every pore, every stray hair, wants to emblazon her into his memory, even as he is certain he will always know her, that even if he is an old man by the time he returns to her, even if she has aged and changed, he will know her. He brushes the hair sticky on her parted lips, his fingers lingering on the warmth of her breath. He is sorry for what he is about to do, what he has done; he will never stop being sorry.

Her nightmares have turned sweet. Suchi can smell sour plums on the horizon. Is it already so late in spring? she murmurs. Later, she will wake and remember yesterday’s careless words; she will lose half a lifetime to regret. But for now: she can feel the warm heft of Haiwen’s presence encircling hers, the tender touch of his hand cupping her face, and she believes he has forgiven her. Her body unclenches. Right before a deep, untroubled sleep claims her, she hears his voice in her ear, kind, reassuring. Soon, he promises her, the plum rains are almost here.

Excerpted from HOMESEEKING by Karissa Chen with permission from Putnam, an imprint of The Penguin Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Karissa Chen