TULSA, Okla. — Parts and labor shortages. Delayed deliveries of new airplanes from Boeing and Airbus. An engine recall. Premature repairs. It’s all piling up, and aircraft engine shops around the world are overflowing.

As travelers boarded planes in record numbers this summer, airline executives waited anxiously for repairs and overhauls of their engines.

The repair and overhaul of engines has swelled from a $31 billion business before the pandemic to $58 billion this year, according to Alton Aviation Consultancy. It’s a cash cow for engine makers like GE Aerospace and the hundreds of smaller specialists that service GE engines, and others made by Pratt & Whitney and Rolls-Royce.

American Airlines‘ solution is to do more of the work itself.

“We just have one customer and that’s American Airlines doing our work,” American’s chief operating officer, David Seymour, said. “We can control our own destiny in that area.”

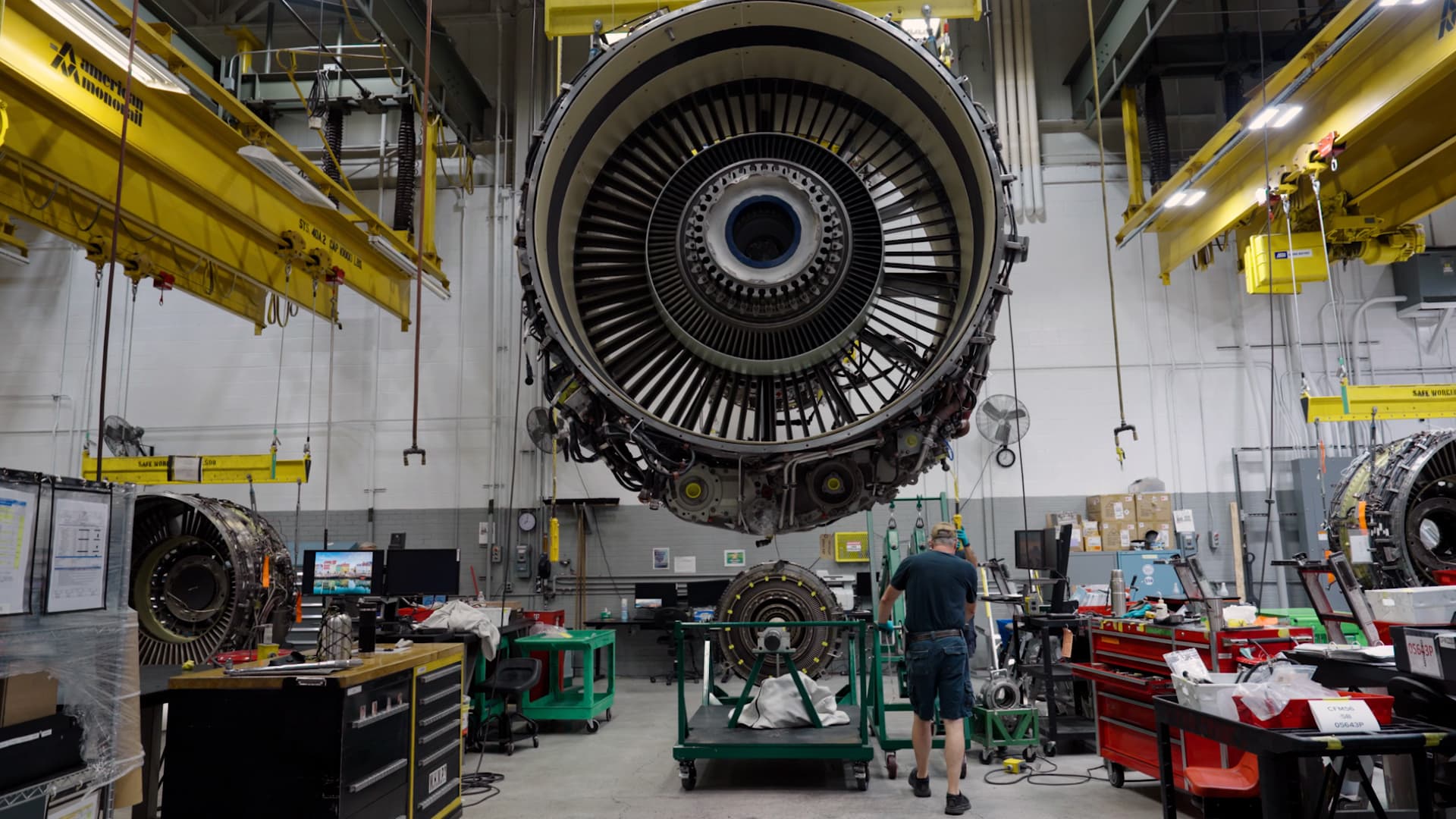

At its bustling engine shop at the airline’s 3.3 million-square-foot maintenance facility at Tulsa International Airport, the largest such space in the world, American is on track to increase its overhauls roughly 60% from 2023 to more than 16 engines a month this year. That’s up from five a month in 2022. It’s added some 200 jobs there, as well more equipment like cranes to hang the 2-ton engines during overhauls.

The work focuses on CFM56 engines, made by a joint venture of GE and France’s Safran. They power American’s older Boeing 737 workhorse jetliners and many Airbus A320s. Those narrow-body airplanes make up the majority of American’s mainline fleet of more than 960 aircraft, according to an annual company securities filing.

“I can get these engines overhauled and through the shop in less than 60 days versus [outside] shops nowadays [are] 120 to 150 days, in some cases north of 200 days,” COO Seymour said.

Bottlenecks abound

Much of the bottleneck in engine repairs stems from the industry’s rocky emergence from the pandemic, when companies shed thousands of skilled workers. Airlines that delayed maintenance during the travel slump then raced to get airplanes into shape to fly when demand snapped back, but faced worker and experience shortages and shortfalls of key items from engine components to aircraft seats.

Meanwhile, Airbus and Boeing are behind on deliveries of new, more fuel-efficient airplanes, forcing carriers, including American, to hold on to older jetliners longer than they planned.

Airbus this summer reduced its aircraft delivery forecast and announced cost cuts as it grapples with supply chain issues and late-arriving landing gear and engines.

“I would also call it the surprise factor for 2024,” Airbus CFO Thomas Toepfer said on a July 30 earnings call.

In addition to supply chain issues, Boeing aircraft have been delayed as the company navigates a safety crisis after a door panel blew out from one of its 737 Max planes midair at the start of the year.

With many engines needing overhauls about every 7,000 flights, keeping older airplanes longer means more routine maintenance and revamps, adding to demand when they’re due to come into the shop. Those weekslong overhauls are exhaustive: They can cost $5 million apiece and can go for double that for wide-body airplanes, according to Kevin Michaels, a managing director at AeroDynamic Advisory.

At American’s shop in Tulsa, workers remove hundreds of parts, replacing life-limited components and cleaning and inspecting others, which includes spraying them down with a a fluorescent penetrant so defects can be seen under a black light.

But key parts are hard to find and they must be flawless. Plus, they’re costly. The dozens of engine compressor blades can go for $30,000 a pop.

On top of that, some newer engines — which run hotter, take in more air and burn less fuel than older types — are coming into engine shops earlier than expected, frustrating airline CEOs.

“There’s no business which can digest not using the key assets to generate revenue,” said AirBaltic CEO Martin Gauss.

The Riga, Latvia-based carrier, an Airbus A220 customer, had to lease planes in recent years to make up for its grounded jets.

“Unfortunately, passengers are not happy when they can’t fly on new aircraft,” he said. “It is an issue which will be over one day. We thought it would be over by now. I would give it another two years and then we are through it.”

There’s another problem that’s clogging up engine shops: A Pratt & Whitney engine recall of some of its narrow-body engines. In light of the ongoing issues, some low-cost airlines, including JetBlue Airways and Spirit Airlines, are deferring new jet deliveries to try to save money.

“It’s kind of a wicked brew that’s had a significant impact on the engine supply chain,” said AeroDynamic Advisory’s Michaels.

Windfall for engine makers

The high demand for engine overhauls has been lucrative for engine suppliers, which make billions from maintaining engines they sell with new airplanes.

GE Aerospace brought in $11.7 billion from engine maintenance, repairs and overhaul in the first half of 2024, making up 65% of its revenue.

“When it comes to engines, it’s a razor-razor blade business,” said Michaels, describing how buying shavers in a drug store can mean repeat business for replacement blades for years. “So the money is made in the aftermarket on the engine business.”

GE Aerospace, which became an independent company in April, said in July that it will invest $1 billion to upgrade its engine shops around the world over the next five years.

Got spares?

For many airlines, there aren’t many alternatives to costly engine overhauls with demand on the rise for replacement engines, especially if the carrier has one type of aircraft or a model that only has one supplier.

Rental rates for engines that match up with both old and new planes have skyrocketed. For example, a CFM56 engine used on the Boeing 737-800 was going for $96,000 a month up from $78,000 in 2017, according to aviation data firm IBA.

Both Pratt & Whitney and CFM engines that power the newer Airbus A320neo airplanes, meanwhile, have logged lease rates of $127,000 per month, up from $80,000 and $85,000, respectively, in 2017, IBA said.

Leasing firms like AerCap and Avolon have been snatching up spare engines because of the high demand.

It is still difficult to get into an engine shop, however.

Delta Air Lines, like American, overhauls, repairs and maintains its own engines. It also does work for other airlines, but CEO Ed Bastian says the shop is full.

“If you’re not on an existing contract, you’re not getting in,” he said in an interview in July. “It would be easier to get into a Taylor Swift concert.”