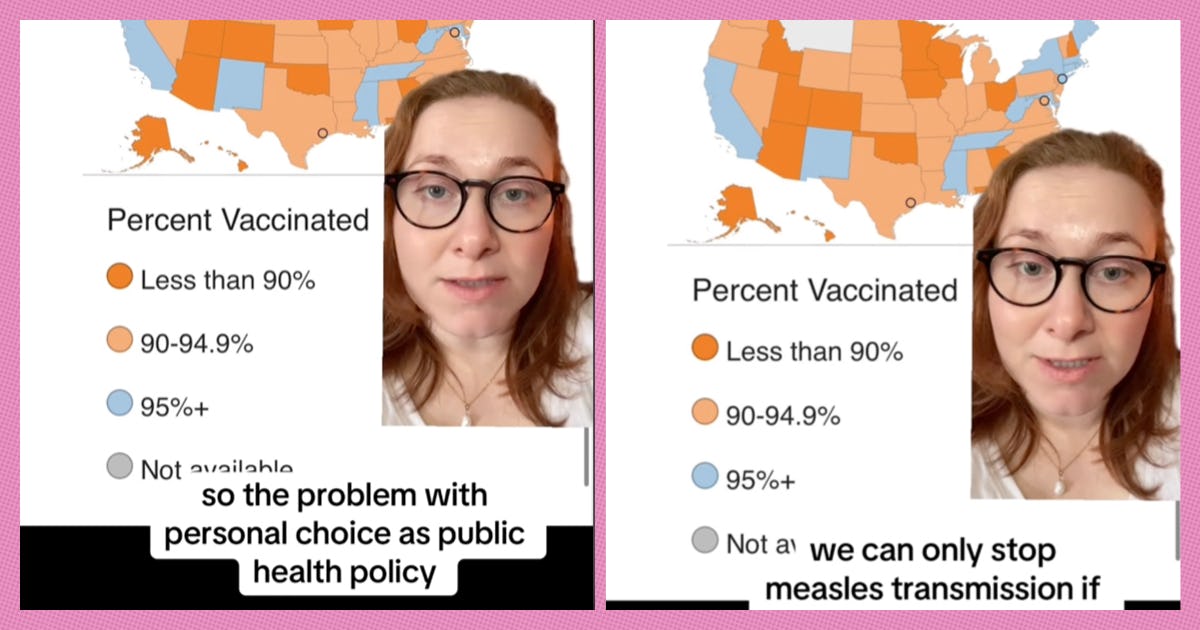

Here’s the good news: overall, the United States boasts pretty high vaccination rates. Even in states that perform lower than average, the overwhelming majority of children are up to date on their scheduled vaccinations that protect them from potentially deadly diseases like mumps, rubella, and polio. But here’s the bad news: in the case of measles, 80% of states are falling short of sufficient protection from sufficient community protection or “herd immunity.”

Kate Harmon Sibe, who posts on TikTok as @kateharmonsiberine, explains…

“The problem with personal choice as public health policy is that it doesn’t work,” they begin. “For example, we can only stop measles transmission if vaccination rates are at 95% or above.”

This is true, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Though some medical institutions, like the Mayo Clinic, put that number slightly lower at 94%. It is also true that, nationally, vaccination rates for the measles-mumps-rubella combination vaccine (MMR), is below either of those numbers at slightly less than 93%.

In fact, during the 2023-2024 school year, the latest for which we have data, kindergarteners in only 10 states — California, Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island, Tennessee, and West Virginia — met the 95%+ threshold. (A round of applause for West Virginia, with a winning 98.3% vaccination rate.)

“Not only does this mean that healthy children will now get measles, which can also be deadly or disabling,” Sibe continues, “it’s especially heartbreaking because it means that medically fragile kids that can’t get vaccinated against measles, who rely on all of the kids around them being vaccinated in order to be protected are no longer safe in public school classrooms.”

This, they note, not only serves to further isolate children with disabilities, but limits their educational opportunities as well.

In 2000, measles was considered eliminated in the United States. However, thanks in part to Andrew Wakefield’s now thoroughly debunked 1998 study linking the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine to autism, vaccination rates began to decline in the United States. As of November 7 of this year, there have been 16 outbreaks and 277 cases of measles. While nowhere near pre-vaccine levels, the number has been steadily increasing over the years.

Until a vaccine for measles became available in 1963, almost everybody contracted the illness by the age of 15. Measles is among the most virulent diseases out there — if 10 people are exposed to the virus, at least 9, on average, will catch it.

For the vast majority of these people (again, mostly children), measles is uncomfortable and unpleasant but not likely to kill you. Symptoms include high fever, cough, runny nose, and, of course, the distinct spotty rash associated with the illness. However, it can be deadly, and because of the sheer number of people who get infected, those death tolls can quickly become truly tragic.

From 1912 to 1922, there were approximately 6,000 measles related deaths per year. From the 1950s to the 1960s, the death toll fell to about 500 out of three to four million cases per year, but still accounted for 48,000 hospitalizations and a thousand instances of encephalitis (a dangerous swelling of the brain).

Even today, measles is an international killer, according to the World Health Organization (WHO): in 2023, 107,500 people died from the illness, mostly unvaccinated and under-vaccinated children.

We all want what’s best for our little ones. And it’s crucially important to look at the data, historical as well as modern trends, to keep all our children healthy and safe.