Right. I feel like, when you’re growing up and you have those little friend groups, they’re always kind of a cult, right? There’s usually one person who’s at the center who everyone else orbits around and wants to be like, or wants attention from.

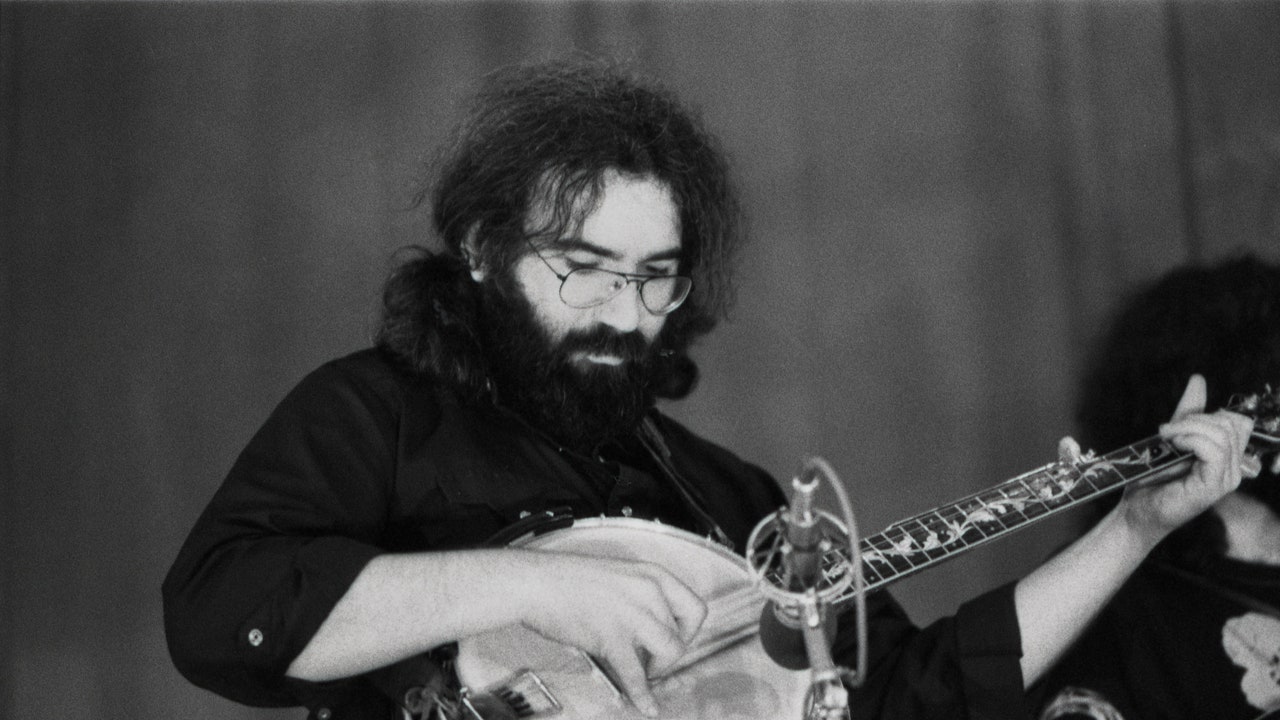

There’s a nucleus. The thing that was important about the Grateful Dead was that usually, in a band, you’ve got your main two [songwriters], and then there’s this ongoing issue about what to do with the other guy—the classic example being George Harrison, or maybe [Rolling Stones bassist] Bill Wyman. Whereas, with the Grateful Dead, Jerry made a point of harassing Weir to write more songs, because he thought that it would be a much better environment if you had multiple voices. And so his leadership was more by example than [about] making decisions.

What was Hunter’s relationship to this book? You said he was glad to share it with you as a document of that time—but what do you think he thought about it, as a book?

Well, you saw what he wrote about it in the early eighties. [In an author’s note from 1982, Hunter said, “I don’t plead the book as a piece of good writing…but as a singular curiosity whose value is wholly unintentional on the part of the writer.”]

Yes. But I wonder how much of that is just him being self-deprecating.

It was the first draft of his work. And obviously he then discovered that his true mode would be in song lyrics, and went forward. But no—it was just part of his personal archive. He said in that document he wrote in the ‘80s that the mistake of the book was that he wrote it, and then he decided it wasn’t profound enough, and he added some set pieces, which I suspect—though I couldn’t prove it, I never asked him—[were] most of those dream sequences, which sort of pad out things and complexify the plot. If there is a plot, really. The whole thing is a portrait.

I write cultural history. Next year I’m coming out with a book that’s about the transition from Beat to hippie, to put it as simply and quickly as possible. And [Jerry and his friends] are one of the fundamental examples of people who were a little too young to be Beat per se, but were sort of late-in-the-game Beats affected by Beat literature, and Beat lifestyle, for that matter. The one thing Hunter makes very clear in the book is a contempt for materialism, which was definitely deep. And so, as a historical document, it’s amazing. It’s kind of perfect. Even at 20 or however old Hunter was, he certainly had the observational skills down, and he wrote an interesting book.