Fede Álverez’s Alien: Romulus is fine. My colleague Jesse Hassenger describes it as a “theme-park ride,” and that’s spot on. A group of Dickensian urchins steal a car and accidentally sneak into an Alien film. It’s an August AC hang that mines the rules and physics of Ridley Scott’s ur-text to deliver a series of interlocking, cool-as-hell, acid-blood-suspended-in-zero-G set pieces. It’s the Scream (2022) of Alien films, a legacy reboot that hits all the beats but largely misses the point.

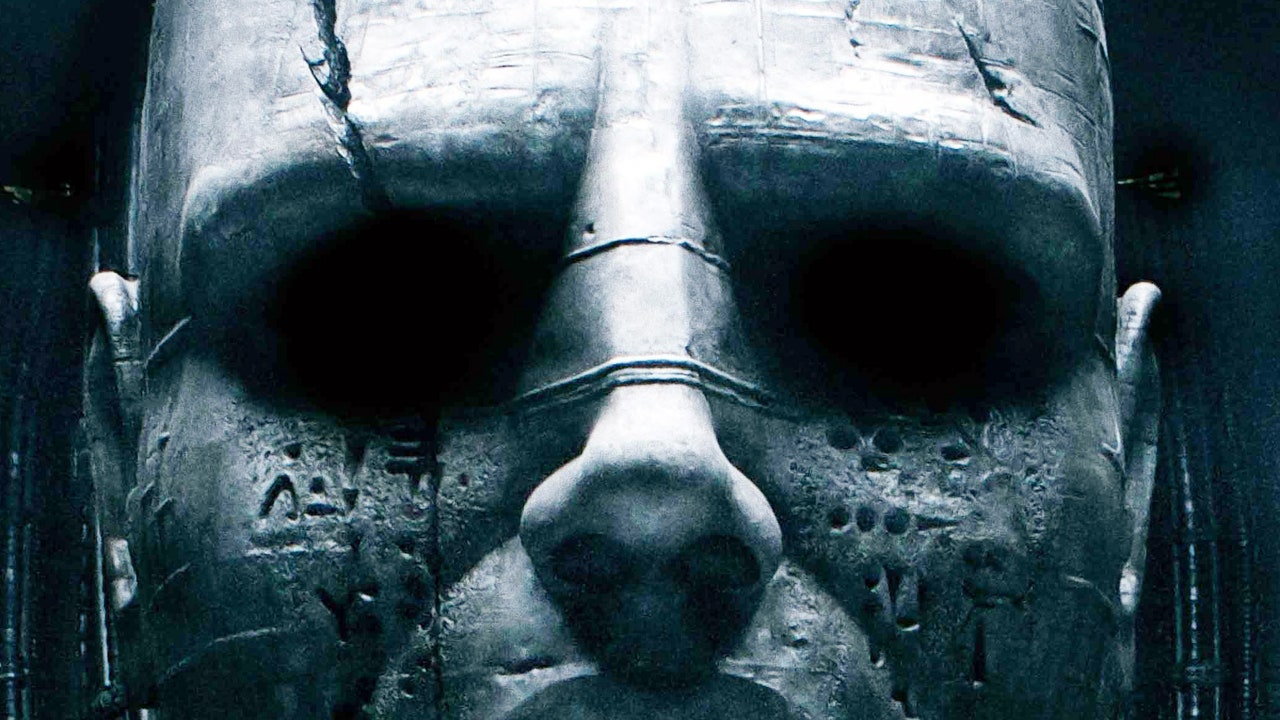

That’s a shame, because of all the exhausted IP stuck to the centrifugal inner wall of the spin cycle that is American Pop Culture, you could argue Alien has evolved into our smartest, most consistent brand. All Alien films are more or less about the same ideas: Greed and hubris, curiosity curdling into self-destructive obsession, Frankenstein’s H.R. Giger-designed unkillable monster returning over and over again to deliver karmic justice.

Ever since the franchise’s forever custodian Sir Ridley dropped out of making the first sequel, leaving the door open for James Cameron to upend the claustrophobic, quiet intensity of the original with his steroidal “What if there were one hundred aliens?” sensibility, the franchise’s addictive hybrid of sci-fi and body horror has been a laboratory, a gym, and an incubator pod for genius directors, who’ve brought a range of styles and ideas to this malleable summer-monster-flick template over 45 years and nine films. (Yes, for the purposes of today’s discussion, the Alien vs. Predator films do count.)

The initial tetralogy of Alien films stuck to a familiar script: A distress call (or warning) goes out from a ship that’s gone missing. A crew of scruffy character actors are awoken from cryosleep to investigate/recover the asset. The overlords of the Weyland-Yutani Corporation catch wind of the nature of the disturbance (or already have some idea of what’s going on) and try to harness the alien for a technological advantage and financial gain. The alien gets loose and runs amok—usually with the help of a nefarious synthetic hellbent against his creators—and humanity narrowly escapes complete annihilation thanks to the superheroism of Ellen Ripley, played by Sigourney Weaver.

After Alien: Resurrection—a weird, gross, occasionally compelling and inventive mess directed by Jean Pierre-Jeunet from a script by Joss Whedon—Weaver exited the franchise, leaving a Ripley-shaped hole the series has never really quite managed to fill. But her departure also created an opportunity to open up the universe and play, a process that ironically begins with the aforementioned and much-maligned, aforementioned Alien vs. Predator in 2004. In the tradition of Deep Blue Sea (a movie about people accidentally inventing super-smart killer sharks while trying to cure Alzheimer’s using…smart sharks), the original AVP is the best kind of dumb genre film: a popcorn flick with a stoned, insane, and almost-interesting premise.

In AVP, it’s revealed that the race we know as Predators—introduced in the 1987 Arnold Schwarzenegger/John McTiernan blockbuster— have been visiting Earth for millennia, and are secretly responsible for the dawn of civilization. They built the pyramids, were worshiped as gods, and created the Alien aliens, known as “xenomorphs,” to train and hunt for sport. The films are not canon, and would be directly contradicted by Prometheus eight years later, but essentially they’re trying to solve the same problem that film grappled with, world-building their way around the Sigourney issue by foregrounding mythology.